Hat Making in Oldland Common

We now say ‘mad as a hatter’, but for the hat makers of Oldland Common, it was the mercury used to improve the preparation of the fur used for making hats and the fine dust in the felt making which caused them to have ‘hatters shakes’ and a form of depression. But drink may have been just as much a hazard. The hatters would drink to quench the tickly particles of fur. Ironically one of the Hicks family from Court Lane was christened ‘Sober’.

Family Businesses

We would expect that coal mining or agriculture would be the largest employment in Oldland Common in the early nineteenth century, but surprisingly most of the villagers were hat or felt makers, making up almost half of the working population at the time of the 1841 Census.

The hat-making was mostly carried out as family-run businesses in their own houses or workshops, with narrow windows to reduce drafts for the felt making. At busy times the whole family including young children would be employed. Important families were:

Allsop, Amos, Andrews, Bailey, Bennett, Bowyer, Brown, Bryant, Chandler, Clark, Colborne, Conolly, Cook, Curtis, Davis, Drew, England, Flook, Fowler, Francombe, Fudge, Hallier, Hicks, Holder, Hollister, Howse, Isles, Jarrett, Lacey, Lowe, Maggs, Morgan, Ody, Pullen, Roach, Short, Simmonds, Scully, Skidmore, Skuse, Smith, Spill, Stone, Taylor, Turner, Williams, Wiltshire

These families frequently intermarried and keenly guarded their independence and the skills in hat making.

Locations

How they made the hats

Most of the hats were of felt construction with beaver or rabbit fur. As well as Oldland Common, the villages of Frampton Cotterell, Winterbourne and Rangeworthy were important centres possibly because of access to the imported beaver fur from Bristol, large nearby rabbit warrens, a source of clean water and low labour costs. Most of the hats were part-finished and sent to Bristol or London for finishing. Many of the lower cost felt hats were exported to be worn on plantations by slaves.

Hat making was relatively well paid but the hatters had many children and often went through a slump in trade. Ann Fry of the Quaker family wrote in 1812 of her visit to the area ‘…we again proceeded to Cabra-heath (Cadbury Heath) and Wollard’s Common (Oldland Common)…amongst the hatters…from the anxiety they labour under to provide for their numerous offspring, it is feared their good desires are too frequently overpowered thereby. From the high price of bread they have been compelled to begin upon their potatoes before their usual time, which it seemed would not carry them through the winter as heretofore’

By the middle the century, local hat making started to decline, not because of any change in the demand for hats, which were worn by everyone outside the home, but for a number of separate reasons. The local hatters staunchly opposed the introduction of non-union labour, they failed to mechanise their processes, the abolition of slavery reduced the demand and finally fashions changed with the introduction of silk hats – these were made of woven silk on felt or gossamer bodies, scoffed at by the felt makers as ‘rag and resin’ but led to a dramatic decline for the hat makers of Oldland Common.

Connection to the Slave Trade

We know that felt hats were made for use in the slave trade, which leads us to question how much of the local output of hats went to bartering for slaves and whether the hat makers knew how their hats were being used. Felt Hat making was the most important local industry at the time of the slave trade. Large numbers were exported abroad from Bristol.

The felt hats made locally were finished to a basic conical form and then finished in Bristol to make a billycock hat which had a rounded crown.

The felt hats made locally were finished to a basic conical form and then finished in Bristol to make a billycock hat which had a rounded crown.

In the colonies in the Americas in many cases slave masters were obliged to give male slaves a pair of trousers and a cap once a year. In the West Indies by 1788, there was a requirement to provide clothing for slaves. For example, each male slave at the beginning of January and August was to receive

`one Jacket made of good found Woollen Cloth, and One Pair of Trowsers made of good found Osenbrig [a strong heavy linen] and if the owner thought proper, a good and sufficient blanket, and a hat or cap.’

In most cases woollen caps were provided but felt hats gave protection in heavy rains.

According to historian, Chris Heal, 3 to 4 million hats, which is about 55% of all hats despatched from the port of Bristol, between 1679-1835, were sent either in the slave ships to West Africa or to the plantations, primarily for slave wear.

The trade was at its peak between 1770-1810. Hats were one of the cargoes on just over half of the West African ships in the years sampled by Heal. At the peak of the trade in 1792 11,500 hats were shipped to West Africa for barter.

Proportion of hats used for barter

Most of the hats involved in the slave trade were hats exported for use by the slaves in the Caribbean, rather than used for barter in Africa for the purchase of slaves. Heal estimates the sales to Africa to be 1 in 10 of the hats exported. This is a small proportion of the overall hats exported (but a small proportion of a very large number).

Where hats were used for barter for slaves, the hats were part of a basket of many other items including brass-ware which came from battery mills such as Saltford.

The Bristol Merchants

Bristol’s slave trading years were generally after 1698, with the end of the Royal African Company’s monopoly, and finished in 1807 when the slave trade in Britain was officially outlawed. The principle suppliers of hats that ended up in West Africa were the Bristol hat firms, Whittuck’s, Owens’, and Ricketts & Ewer.

Much of the export was carried out by John Anderson, James Rogers, James and Thomas Jones, Thomas King and later by his sons’ company Richard and William King. Richard became Mayor of Bristol and his great grandfather, John King, was a previous mayor. Bristol Merchants had forged good trading relations in specific regions of West Africa, in Calabar, Bonny and Angola. The majority of those enslaved and taken to these ports were captured in raids and wars by local African leaders.

John Cary, a Bristol merchant, described the African trade in 1695, as:

`…most advantage to this kingdom of any we drive, and as it were all profit traffic in negroes being indeed the best Traffick the Kingdom hath’.

Research by the historian David Richardson suggests that in the late eighteenth century at least 40 per cent of the income of Bristolians derived from slavery-related activities.

Hats for Slaves

The historian Madge Dresser estimates 486,000 enslaved Africans were delivered by Bristol to the New World from 2,008 voyages. It is generally accepted that about a quarter died en route.

A number of business archives survive, some like those of James Rogers of Bristol with considerable detail about overall investment and individual cargoes. An example of such records is the snow (a square rigged vessel with two masts) ‘Molly’, which sailed for Bonny in Nigeria in 1750 to buy ‘negroes and elephant teeth’ for the owners, Richard Meyler & Company.

Among the cargo was one cask of five dozen felt hats and three men’s gold laced hats at 12s 3d each, bought from Bristol hatters Charles Whittuck and Thomas Owen. The ship’s accounts suggest a cargo of over nineteen dozen although some hats may have been destined for other ships:

Dresser writes of two Bristol vessels which, in 1679, carried ‘not only the various types of cloth popular with West Africans, but the felt hats which were an indispensable commodity on slaving ships after 1698. Bristol ships sailed with felt hats for Virginia, Georgia, Africa and the West Indies; delivered by the beginning of the sugar-cutting season. Sir John Moore Lord Mayor of London) described the plantation trade as ‘booming’ and that light and well waterproofed hats gave protection from sun and rain.

Hats for Bargaining

Fourteen cargoes of Bristol slavers that sailed from 1725 to 1804 were examined by Dr Heal to discover a typical cargo. Although 103 goods are included in the current sample, the items are not disparate and resolve easily into main categories of alcohol, cloths, clothes, household goods, metals, ornaments, tobacco and weapons.

A few high quality hats were from London, but the great majority came from around Bristol. Despite the low value of the slave trade to the city’s hatters, hats were seen as an essential part of the barter basket by the slavers and their customers.

Witting or unwitting

It is difficult to know how much the makers of felt hats knew about how their products were traded. Because of the very large numbers of hats which were used for slaves, it is likely that the hat makers knew where the hats would end up, but the question is whether they knew their hats would be used to buy slaves. They made the hats under a contract from a master, outside the area, and took no part in how they would be marketed.

We know that not only did they read the local Bristol newspapers, but we have evidence that George Ollis, a well-known hatter who had a small factory in North Street, Oldland Common spoke out strongly against slavery. George Ollis was sacked from his job along with five other hatters because he did not vote in the way his boss wanted in the election of 1831/2. They were among the few who could vote. The men had refused and were dismissed in what became known as ‘The Case of the Oldland Hatters’. Ollis said he was pledged for the Whig candidates:

‘because they are friends to reform, the cause of people, and principally that they are for the abolition of slavery’.

We can be sure that the six men felt very strongly that slavery was wrong because in losing their jobs for this cause they had put their families at risk of deprivation.

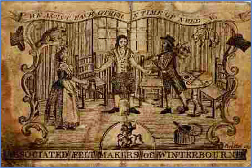

The hat makers were also strong supporters of a union (the Felt Makers’ Society of The United Kingdom) that was very concerned about the rule of law, ethics and activity in local poor relief.

It is clear that a large proportion of the export sales of local hats was connected with the slave trade. While the majority of the hats were for use by slaves in the Caribbean, hats were indeed used to barter for slaves in Africa.

Evidence shows that some local hat makers (at least by the early nineteenth century) were adamantly against the slave trade – so much so that they were prepared to lose their jobs in the support of abolition.

Further, they would have had no control on the end-use of their hats. They sold to a master, who sold to a hat finishing business, who sold to the merchant shippers.

We can conclude that local hat makers were unwitting participants in an abhorrent trade and that prominent local hat makers were steadfastly against slavery.

Many thanks to Dr Chris Heal for much of the content of this page. His doctoral thesis is available: The felt hat industry of Bristol and South Gloucestershire, 1530-1909. EThOS ID 566215.